Focusing on feline cognitive dysfunction

10 December 2025

Gemma L Walmsley received PetSavers funding for a student research project which was part of the feline healthy ageing clinic at the University of Liverpool. Student Reid Shrubsole undertook the project entitled Evaluation of feline cognitive dysfunction in a prospective ageing and welfare study in cats (CatPAWS), with support from Alex German, Kelly Eyre, Eithne Comerford and Gina Pinchbeck, and describes her experience here.

Cognitive dysfunction syndrome, also known as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in humans, is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by deteriorating cognitive function and altered behaviour associated with pathological abnormalities in the brain.1 Of the veterinary species, cognitive dysfunction has been best studied in dogs, and the similarities with human AD mean that this species is used as an animal model for the condition.2 Comparatively little is known about feline cognitive dysfunction (FCD), but neuropathological changes are similar and include the deposition of beta-amyloid in the brain and hyperphosphorylation of tau proteins.3,4 Prevalence increases with age and studies have estimated signs of dementia in approximately 28% of cats between 11 and 14 years of age, increasing to 50% in cats aged 15 years or older.5

Cats are popular pets which often live long lives, and behaviour changes are one of the most commonly reported problems associated with ageing.6 There may be many causes for age-related changes in behaviour, including FCD which is typically associated with clinical signs described by the acronym VISHDAAL: vocalization, altered interaction with owners, altered sleep–wake cycles, house-soiling, disorientation (spatial and/or temporal), alterations in activity, anxiety, and/or learning/memory deficits.4 The diagnosis of FCD can be challenging, partly because it relies on owners recognizing and accurately describing the changes observed in their cat to their vet, and some of the earlier, more subtle signs can be difficult to distinguish as signs of ill health.

Clinically, FCD is a diagnosis of exclusion that can only be made once other possible medical, neurological and behavioural causes have been ruled out. The condition has a considerable impact on the wellbeing of cats and their owners due to emotional distress and disturbed sleep.7 There is no cure, although studies in dogs and humans have revealed that early recognition and treatment can improve signs and slow decline.

The Cat Prospective Ageing and Welfare Study (CatPAWS) commenced at Liverpool in 2016 and aided by the establishment of the Royal Canin Feline Healthy Ageing Clinic, has already generated a wealth of epidemiological data about normal feline ageing and associated diseases.6 Cats enrolled in the study (240 to date) are followed closely with questionnaires and clinical assessments every 6 months, therefore this is an ideal population to monitor for changes in behaviour and cognitive function over time.

Project aims

The goal of this student study was to identify reliable tools to assess feline cognitive function, thereby allowing us to prospectively monitor cognitive decline in ageing cats and collect epidemiological data on clinically significant FCD and other systemic and neurological conditions that also affect the forebrain.

Our aims were to:

- Analyse relevant questionnaire data on behavioural changes associated with cognitive dysfunction already collected during CatPAWS from the 240 enrolled cases

- From this and published studies, develop a set of additional questions that would more thoroughly evaluate cognitive dysfunction in cats

- Develop and pilot a focused neurological assessment that can be incorporated into follow-up examinations for monitoring.

Questionnaire evaluation of cognitive dysfunction in ageing cats

Owner questionnaires are often used to aid the diagnosis of behavioural problems, with several having been developed for use in dogs with cognitive dysfunction,8 including the canine dementia scale CADES.9 Recently, MacQuiddy et al.10 used a questionnaire for the diagnosis of FCD in a US population of cats to research risk factors.

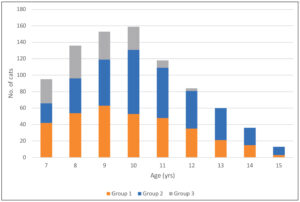

We conducted an epidemiological study using questionnaire data generated from CatPAWS. Answers to questions relating to the VISHDAAL behaviours associated with FCD (Table 1) were extracted into spreadsheets and used to group the cats into those with at least one behaviour consistent with FCD and no underlying condition (Group 1), those with at least one behaviour consistent with FCD and an underlying medical condition (Group 2) and those with no behaviours consistent with FCD (Group 3) (based on MacQuiddy et al., 2022) (Figure 1).

Table 1: Signs associated with feline cognitive dysfunction assessed by the CatPAWS questionnaire

Figure 1: Histogram showing the numbers of cats at each age grouped into those with at least one FCD-associated behaviour without (group 1) and with another underlying condition (group 2), and those with no behavioural changes reported (group 3).

Two hundred and forty cats were enrolled, of which five were excluded from subsequent analysis due to their uncertain age, leaving 235 cats aged between 6–11 years at the time of the first questionnaire. At enrolment, 141/235 cats (60%) displayed at least one of the VISHDAAL behaviours; however, 65 of these (28%) were known to have a potential underlying problem, leaving 32% (76/235) of cats with behavioural changes consistent with FCD but no other reported conditions that could have explained these changes. No statistically significant association could be found between environmental factors at enrolment and the development of signs of cognitive dysfunction.

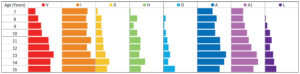

Follow-up questionnaires were completed every 6 months for a median of 12 months (range 0–78 months). By 13 years, all cats displayed at least one sign of cognitive dysfunction, whilst 39/60 (65%) had another potentially underlying condition (see Figure 1). The most reported behaviours were increased affection or attention (seen in 72–100% of cats with FCD depending upon age), followed by altered activity (45–86%), anxiety (35–80%) and vocalization (21–67%) (Figure 2). The proportion of cats displaying each behaviour and the number of behaviours displayed by each cat increased with age: in cats from Group 1 aged 7 years old, 43% only showed signs in one category and 26% showed signs in ≥3 categories; whereas by 13 years of age, 86% showed signs in ≥3 categories.

Figure 2: Visual representation of the FCD signs seen within group 1 cats at each age. V = vocalisation, I = altered interaction with owners, S = altered sleep–wake cycles, H = house soiling, D = disorientation (spatial and/or temporal), A = alterations in activity, A1 = anxiety, L = learning/memory deficits.

Use of a targeted neurological assessment in cats presenting for follow-up examinations

A limited neurological assessment was added to the current examination that includes physical and orthopaedic examinations, blood pressure measurement and blood tests. Gait observation and cranial nerve assessment were successfully conducted in most cats (12/13) but the assessment of postural reactions was only possible in 6/13. One case had signs consistent with cognitive dysfunction, with the menace response being bilaterally reduced. Lateralizing neurological deficits, which could have indicated a focal forebrain lesion such as a meningioma, were not detected in any of the cases. None of the cats explored the room sufficiently to find a scented treat (a smear of Lick-e-Lix).

Conclusions and future plans

Questionnaires can be an inexpensive and informative tool but there are limitations to their use in a clinical setting, not least because many other medical, orthopaedic and neurological conditions can also cause behavioural changes. Signs of cognitive dysfunction were commonly reported in this feline population, whilst the proportion of cats with at least one abnormal behaviour increased with age. However, many cats also had a potential underlying medical or orthopaedic condition.

The most common behavioural changes were increased attention or affection, which was reported early on in a large proportion of cases. It is possible, therefore, that this increased interaction with their owners happens normally during feline ageing as they become calmer and spend more time at home and undertake less outside activity. This finding may not have been reported in previous studies of FCD because owners are more likely to notice and seek advice for problem behaviours that negatively impact their own quality of life.11

Follow-up questionnaires seemed to indicate that signs were progressive, not least given that more abnormal behaviours were displayed as cats aged. However, it became clear during analysis that a new questionnaire should be developed for FCD that also collects information about the frequency of observed behaviours. This would give an output score reflecting the severity of cognitive dysfunction for monitoring purposes rather than a binary ‘yes–no’ FCD diagnosis. This finding is similar to popular questionnaires developed for canine cognitive dysfunction.8,9 Therefore, in the process of conducting this study, a new questionnaire for the diagnosis of FCD and the grading of clinical sign severity was developed; this will now be piloted in the Feline Healthy Ageing Clinic and tested to monitor our population of cats with the aim of publishing it for clinical use.

Our ultimate goal is to be able to recognize this condition early, to allow us to implement management strategies and trial novel treatments to improve clinical signs and slow progression in affected cats for the benefit of our patients and their owners. More work on FCD is required in order to understand this condition better, not least the impact of management strategies, which might include environmental modification and enrichment, dietary supplementations, specific diets and medication.4,11

My experience with the summer research project

The greatest challenge during this project was the tight time frame to get the work completed. We discussed our goals at the beginning and, after 3 weeks of data analysis using Microsoft Excel, the realization that half my time was gone and there was still so much to do was a little nerve-wracking! Nonetheless, a real highlight has been seeing all the cognitive questionnaire data come together to tell a story about how FCD affects the behaviour of ageing cats, and then hearing directly from owners their viewpoint of the impact this can have on their daily lives. It naturally makes you feel the work you are doing is important.

In my opinion, it is crucial for veterinary professionals to have good research skills, since this will help them to provide the best care for their patients, not least since knowledge is constantly evolving. I feel incredibly lucky to have been able to devote time to acquiring such skills, and feel as though I have contributed to that ever-growing pool of knowledge. Acquiring these skills was made possible by a BSAVA PetSavers student research project grant, and I would highly recommend anyone who is thinking of applying to just go for it!

Acknowledgements

Reid Shrubsole was financially supported by a BSAVA PetSavers student research project, whilst the CatPAWS project is funded by Royal Canin, and this funding also includes financial support for the post of KE at the University of Liverpool. Alex German is an employee of the University of Liverpool whose position is currently funded by Royal Canin. He has also received financial remuneration and gifts for providing educational material, speaking at conferences and consultancy work.

About the author

References

- Hardy JA and Higgins GA (1992) Alzheimer’s Disease: The Amyloid Cascade Hypothesis. Science 256(5054), 184–185

- Cory J (2013) Identification and management of cognitive decline in companion animals and the comparisons with Alzheimer disease: A review. Journal of Veterinary Behaviour 8(4), 291–301

- Landsberg G, Nichol J and Araujo J (2012) Cognitive dysfunction syndrome: a disease of canine and feline brain aging. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice 42(4), 749–768

- Sordo L and Gunn-Moore D (2021) Cognitive Dysfunction in Cats: Update on Neuropathological and Behavioural Changes Plus Clinical Management. Veterinary Record, 188

- Gunn-Moore D, Moffat LA and Christie EH (2007) Cognitive dysfunction and the neurobiology of ageing cats. Journal of Small Animal Practice 48(10), 546–553

- Dowgray N, Pinchbeck G, Eyre K, Biourge V, Comerford E and German AJ (2022) Aging in Cats: Owner Observations and Clinical Finding in 206 Mature Cats at Enrolment to the Cat Prospective Aging and Welfare Study. Frontiers in Veterinary Science9, 859041

- Powell L, Watson B and Serpell J (2023) Understanding feline feelings: An investigation of cat owners’ perceptions of problematic cat behaviors. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 266, 106025

- Haake J, Meller S, Meyerhoff N, Twele F, Charalambous M, Talbot SR, and Volk HA (2024) Comparing standard screening questionnaires of canine behavior for assessment of cognitive dysfunction. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 11, 1374511

- Madari A, Farbakova J, Katina K et al. (2015) Assessment of severity and progression of canine cognitive dysfunction syndrome using the CAnine DEmentia Scale (CADES). Applied Animal Behaviour Science 171, 138–145

- MacQuiddy B, Moreno J, Frank J and McGrath S (2022) Survey of risk factors and frequency of clinical signs observed with feline cognitive dysfunction syndrome. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery, 24(6), 131–137

- Černá P, Gardiner H, Sordo L, Tørnqvist-Johnsen C and Gunn-Moore DA (2020) Potential Causes of Increased Vocalisation in Elderly Cats with Cognitive Dysfunction Syndrome as Assessed by Their Owners. Animals (Basel) 10(6), 1092